Without it, US companies risk being complicit in the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya

This article is re-posted from the Truman National Security Project Doctrine Blog. The original article can be accessed here.

In 2017, at the onset of an ethnic cleansing campaign in Myanmar, the Trump Administration quietly eliminated the only mechanism we had to prevent multinational corporations from contributing to the slaughter. The so-called Burma Responsible Investment Reporting requirements mandated that U.S. companies report publicly on how they intended to prevent their Burmese operations from contributing to human rights violations. The program began in 2013, shortly after economic sanctions were lifted on the longtime military-led nation. As foreign investment began to flow into Myanmar, companies including Coca-Cola, Gap, Caterpillar, and Chevron reported on their protocols for managing human rights risks.

Some of the reports were terrible. Crowley Marine Services, a shipping subcontractor to oil companies, limited its reporting on human rights due diligence to a single sentence: “Crowley Marine Services maintains a comprehensive series of policies and procedures that address environmental and safety issues, as well as human and worker rights.” This was broadlymocked, and company reports became increasingly in-depth after that.

On the other hand, some reports were profoundly impactful, such as those by Coca-Cola, who spent four years on supply chain due diligence before sanctions were lifted. Such efforts, though time consuming, were necessary; as Brent Wilton, Coca-Cola’s director of workplace rights, described it: “There was no transparency there at all…there was a reticence of the government to release any information at all.” For instance, a single company could have four different names, depending whether it was interacting with Thai, Chinese, Burmese, or English speaking counterparts. In other words, Coke might think it had safely avoided a relationship with a dodgy partner, only to learn that it was in talks with that same company operating under a different name. Determining ownership of a company was equally challenging: While trying to avoid doing business with particular military leaders on U.S. sanctions lists, Coke had no way of knowing who owned various businesses because there were no public records documenting ownership structures. For example, after years mapping out its in-county partnerships before opening shop, Coke learned one year into its investment that one of its partners also ran a dodgy side business in jade mining.

When Global Witness found the jade mining connection, it had a ready listener in Coke. Wilton says that the reporting requirements “drove a lot of conversations that wouldn’t have happened otherwise,” both internally at Coca-Cola and with partner companies. For a brief period, all the right pressures were in place to expose human rights violators and enable companies to operate with respect human rights in Burma. However, that window is now closing, and the U.S. government must take some responsibility.

The end of the reporting requirements coincided with the ramp-up of a genocide campaign against the ethnic minority Rohingya population in Rakhine state, western Myanmar. When human rights risks were at their highest, the oil and gas companies who hold petroleum blocks offshore of Rakhine State no longer had to report on how they kept their investments from the military apparatus conducting the slaughters; instead, human rights advocates and financial analysts began conducting their own due diligence.

For instance, Nobel Laureates gathered in Oslo specifically to pressure Statoil to withdraw from its oil blocks in the country. Shell secretly flagged Myanmar as a reputational risk as early as June 2015, when an early rash of Rohingya killings occurred, and faced substantial public backlash when that analysis was exposed by activists. In August 2017, shareholders sent a letter to Chevron calling for a re-evaluation of its Myanmar business. Two months later, investors representing more than $53 billion in assets under management sent letters to six additional oil and gas companies asking them to “reassess their dealings” in Myanmar in light of human rights violations.

Chinese and American companies have not acted on these pressures, but this spring, Shell, Statoil (Norway), and Reliance (India) returned their petroleum blocks to the Myanmar government, partly in response to reputational risksposed by being associated with a genocidal government.

Given the recognized corporate reputational risks associated with Myanmar’s ethnic cleansing undeniable, it is not totally clear why the reporting requirement was eliminated. Coca-Cola, for one, was candid about the value of the program, writing a public letter in support of it shortly before it was canceled. 49 other organizations joined Coke, writing independently to the Department of State to publicly support the requirements; only one, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, opposed it.

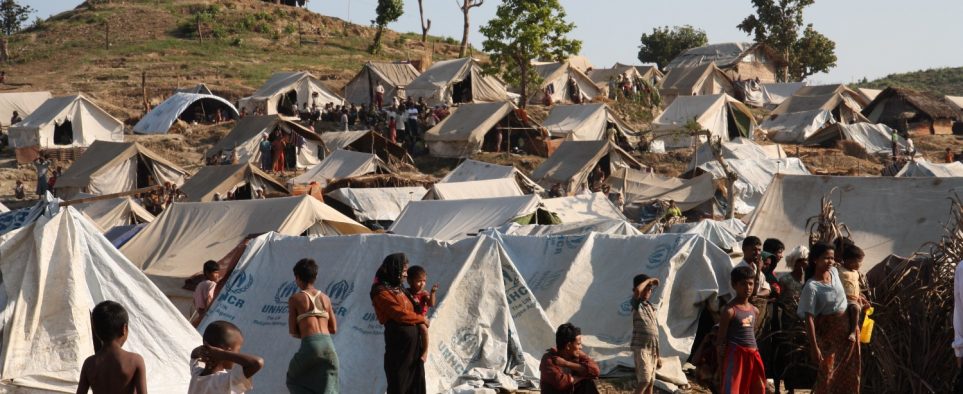

The then-incoming administration just may not have had interest — but the consequences are now clear. An estimated 700,000 Rohingya have been driven from their homes by the military, their villages burned, and their neighbors raped, tortured, and murdered. This carnage has been underwritten with the help of multinational corporations. Last week, for example, Kirin was exposed for having donated $30,000 directly to the military leaders carrying out the atrocities.

The Rohingya are not the only ones affected, however: Ethnic violence has also escalated against Shan and Kachin ethnic minorities. Meanwhile, the American Embassy’s website has scrubbed all record of the human rights reporting requirements, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Myanmar is seeking to ramp up investment. At the height of the ethnic cleansing last year, it brought a delegation of U.S. bank representatives to Yangon, aiming to have the remaining U.S. sanctions removed.

Against the resounding silence from so many U.S. companies and agencies in the face of human rights violations, Coke is an exception. It remains both heavily engaged in Myanmar and circumspect about the risks. Coke has only six in-country suppliers because it cannot be confident that, for example, sugar suppliers are ethical. As Wilton points out, “The environment is not great and has deteriorated.” When Coke’s public affairs team in Yangon sought to bring aid to Rohingya refugees, authorities wouldn’t permit the company to enter Rakhine state; consequently, Coke had to bring aid through Bangladesh to reach the displaced populations.

Yet, even they have scaled-back their resources dedicated to human rights in Burma, Wilton pointed out that he just couldn’t muster the resources to write a report akin to those he wrote when reporting was mandatory; therefore, though Burma is included in Coke’s seminal human rights report, the overall report is a far cry from what it was under former reporting requirements.

The Burma Responsible Investment Reporting Requirement was a powerful tool with low cost. Yet, without so much as a platform for publishing such reports, most U.S. companies are not protecting their reputations or the lives of Burmese citizens. It would be feasible to keep this blood off our hands preemptively. It will be impossible to wash our hands of the violence after it occurs.